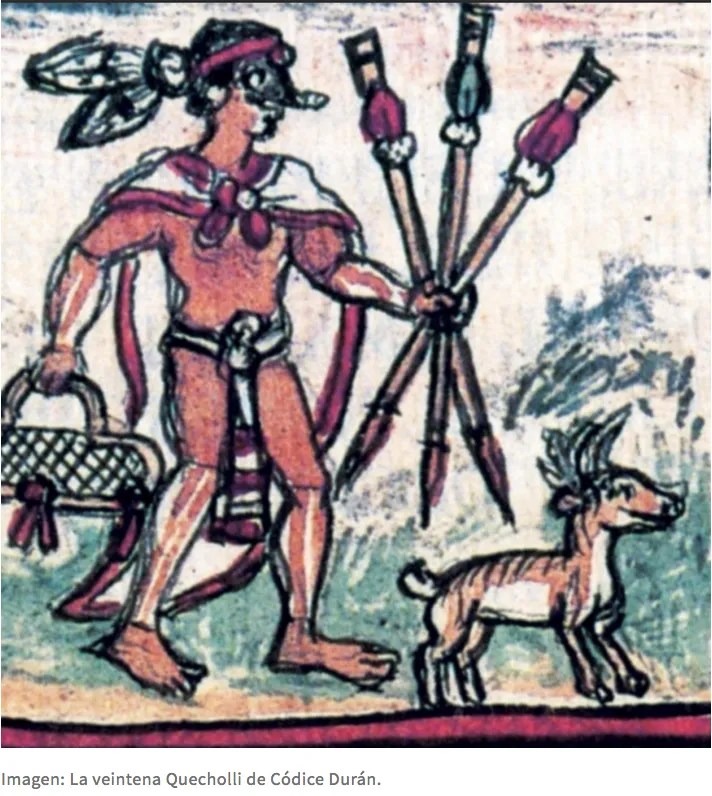

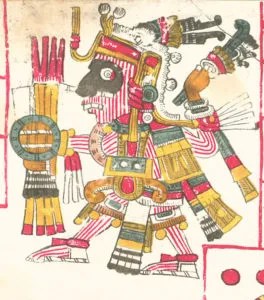

The feast of Kecholli is named for the roseate spoonbill, a bird with resplendent pink feathers that migrates south into Mexico during the winter months. The word Kecholli can be translated as “rubber neck” in the Nawatl language. The feast was held in honor of Kamaxtli/Mixkoatl, the lord of the hunt, who is depicted in the codices painted in red stripes and holding his hunting instruments. The first several days of the month were used to craft the arrows, darts, and spears that would be used in the upcoming hunt. During Kecholli we give thanks to the deer and the other creatures who give up their lives for our sake, so that we can eat their flesh and flourish.

Most of us live in an urban environment, in which hunting is an activity which is no longer relevant to our daily lives. For the consumption of meat, we rely on farm animals. In the past, the only domestic animals were dogs and turkeys. But today, many of us eat cattle, pigs, and chicken as well. While these beings were unknown to our ancestors, it is appropriate to give them honor during Kecholli, for they, like us and the deer which our ancestors hunted, are in possession of consciousness and suffer and die for our sake. Just as our ancestors gave thanks and praise to the deer, we must give thanks to those creatures who die for us and become our flesh. We must always remember that they are our brothers and are as beloved by the Teteoh as we are.

Hunters embark on the ceremonial hunt during Kecholli, from Primeros Memoriales

Because it is the feast of the hunt, it is also the feast of arrows. We give honor to the arrows who fly to their prey and bring down our brothers the deer, rabbit, and waterfowl. We give the arrows offerings, who are the instrument of death which brings us life. If you are a hunter, you ask the arrow, or the bullets and gun, to fly straight and true, and to bring death without suffering. If you are not a hunter, the arrow represents the death of the beings you consume. Remember that our ancestors practiced the honorable harvest. They gave thanks to the corn, and to the animals who die for our sake, and honored them as brothers. Perhaps this is a time to refrain from eating meat, and to contemplate the terrible suffering our animal brothers and sisters suffer, in the factory farms in which they live and die. Through the symbol of the arrow, it is a time to remember the honorable harvest, and to seek ways to return to the wisdom of our ancestors, who understood that the dying creature is not simply an animal we eat, but a brother who died so that we might live.

During Kecholli, we give offerings to soldiers who have died in war. They were chosen by Tonatiuh, Our Lord the Sun, and descend to join us at our altars. We honor them for their sacrifice.

Finally, we give honor to Witzilopochtli during Kecholli, who is a manifestation of the Sun. Kecholli means “spoonbill,” which is a kind of water bird. The Roseate Spoonbill is pink, and its feathers were used to adorn the regalia of the Lords of the Sun. Therefore, the name of the metztli refers to the Sun, light, and fire. During the dry season of Tonalko, Witzilopochtli, who is fire and light, reigns, and we give Him honor.

From the Florentine Codex (Book 2, pages 25-26):

“When they made the arrows, for a space of five days all took blood from their ears, and with the blood they anointed their temples. They said that they did penance in order to go to hunt deer. Those who did not bleed themselves had their capes taken away as punishment. No man lay with his wife on those days; neither did the old men nor the old women drink pulque; because they did penance.

At the end of the four days during which they made the arrows and darts, they made a number of very small arrows, and bound them in fours with bundles of four torches. These they offered upon the graves of the dead. They placed also, along with the arrows and torches, two tamales. All this remained for a whole day upon the grave, and at night they burned it and performed many other ceremonies for the dead on this same feast.

On the tenth day of this month, all the Mexicans and Tlatelolkans went to those mountains which they call Zakatepek. And they say that this mountain is their mother. On the day that they arrived, they made huts or cabins of grass, and they lit fires, and nothing else did they do that day. Next day, at dawn, all broke fast and set out for the country and formed a great wing, wherewith they surrounded many animals deer, rabbit, and other animals — and little by little they kept coming together until they rounded up all of them. Then they attacked and hunted, each one what he could.

When the hunt ended they slew captives and slaves on a pyramid which they call Tlamatzinko. They Bound them hand and foot, and carried them up the steps of the pyramid as one carries a deer by the hind and forelegs to slaughter). They slew with great ceremony the man and the woman who were the ixiptla of the god Mixkoatl and of his consort. They slew them on another pyramid which was called Mixkoatkopan. Many other ceremonies were performed.”

Modern Interpretations of Etzalkwaliztli (adapted with permission from the work of micorazonmexica)

The ceremonies of Kecholli are different for hunters than for other people. If you are a hunter, it is a time to give honor to the instruments of the hunt, to the bow and arrow or the gun and bullet, which did not exist in the world of our ancestors, but which is the way most hunters now kill our animal brothers. They possess power and should be thanked for the work they do. If you are an arrow maker, it is the time to make your arrows, and to make them offerings. They ask of you your own blood, in payment for the blood of the animal brothers they are to spill, pulled from the earlobes, fingers, and other fleshy parts, with maguey thorns.

If you are not a hunter, arrows or paintings of arrows should nonetheless be placed on the altar. The arrows represent the deaths of our animal relatives and remind us of their suffering and death for our sake. On the altar are placed images of the animal beings we eat, of the deer, cow, turkey, chicken, fish, and other creatures. They have died for us, and are one with us, as part of our very flesh. We adorn their images with ribbons and paper flags and streamers, and beg their forgiveness for the suffering they endure, and thank them for their gift of life.

During Kecholli, warriors who have died in battle, or others who have died in the defense of a just cause, descend to the earth in the form of hummingbirds and honor us with their presence. To recognize their sacrifice, we make small arrows, no more than the length of the hand, and tied to form a cross. We place these upon the altar, together with offerings of sweet tamales. At the end of Kecholli these crosses are burned, and if we have a loved one who died in battle, the ashes are buried at their grave.

If a loved one has died as a soldier in war, we take a dry maize-plant, and tie it with 9 ribbon knots. The maize-plant is adorned with paper flags and streamers, and is dressed in a paper tilma, maxtlatl, and shield, or with the uniform of the dead soldier. A clay or paper hummingbird is hung from the plant, and bunches of white feathers which symbolize sacrifice. The soldier has become one with the maize and nourishes their community with their death. During Kecholli they descend to the altar from their home in the paradise of Our Lord the Sun and join us in our feasting. We give honor to them, and to all the brave men and women who have died in the defense of justice, or who died after having dedicated their lives to such causes.

The altar is hung with moss, and on it, in addition to the arrows and offerings for the dead, are placed images of Mixkoatl, Cloud Serpent, who is the Lord of the Hunt, and of Witzilopochtli, the Hummingbird on the Left, who is a warrior and a Lord of the Sun. Those who battle in defense of just causes pray to Witzilopchtli to guide them, and hunters and farmers who raise and kill our animal brothers pray to Mixkoatl to guide them towards the sustainable harvest. Beside Mixkoatl is placed an image of Koatlikwe, Serpent Woman, who is His wife. He is the stars in the milky way, while She is the earth, and together They bring us all life. Her image is dressed in paper regalia, and paper weaving instruments are placed before Her. Her paper clothes and weaving tools are burned at the end of Kecholli by the women of the household, and honor is given to Her, for She weaves our destiny.