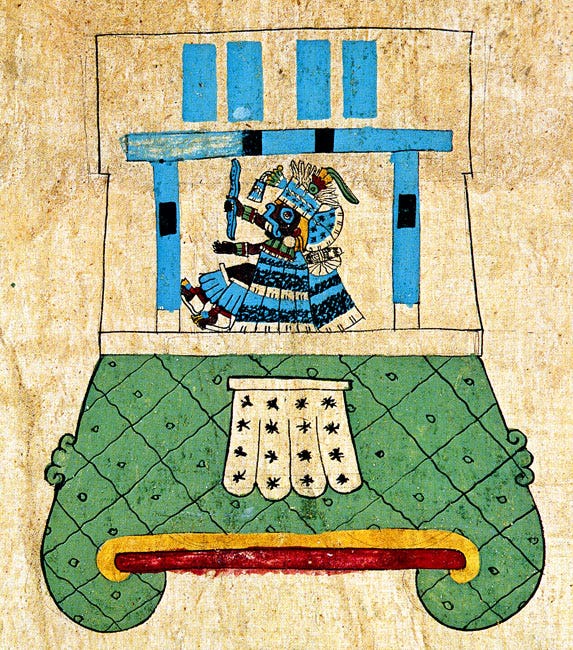

Atlakawalo marks the end of Tonalko, signaling the division of the Xiwitl (solar year) into two halves, and bringing the onset of festivals and ceremonies of Xopan, the rainy season. It is a time to honor Tlalok, Our Lord the Rain, and his helpers, the Tlalokeh. Resting on top of the sacred mountains lies a misty paradise governed by Tlalok, known as Tlalokan. Tlalok sends His emissaries, the Tlalokeh, to the cardinal directions, carrying with them the life-giving rains. These rains, while essential, also possess the potential for harm, manifesting as floods, hurricanes, hail, or drought. Hence, during Atlakawalo, we make offerings to Tlalok so that he might grant us gentle rains that will rejuvenate the fields and uplift our people with joy.

From the Florentine:

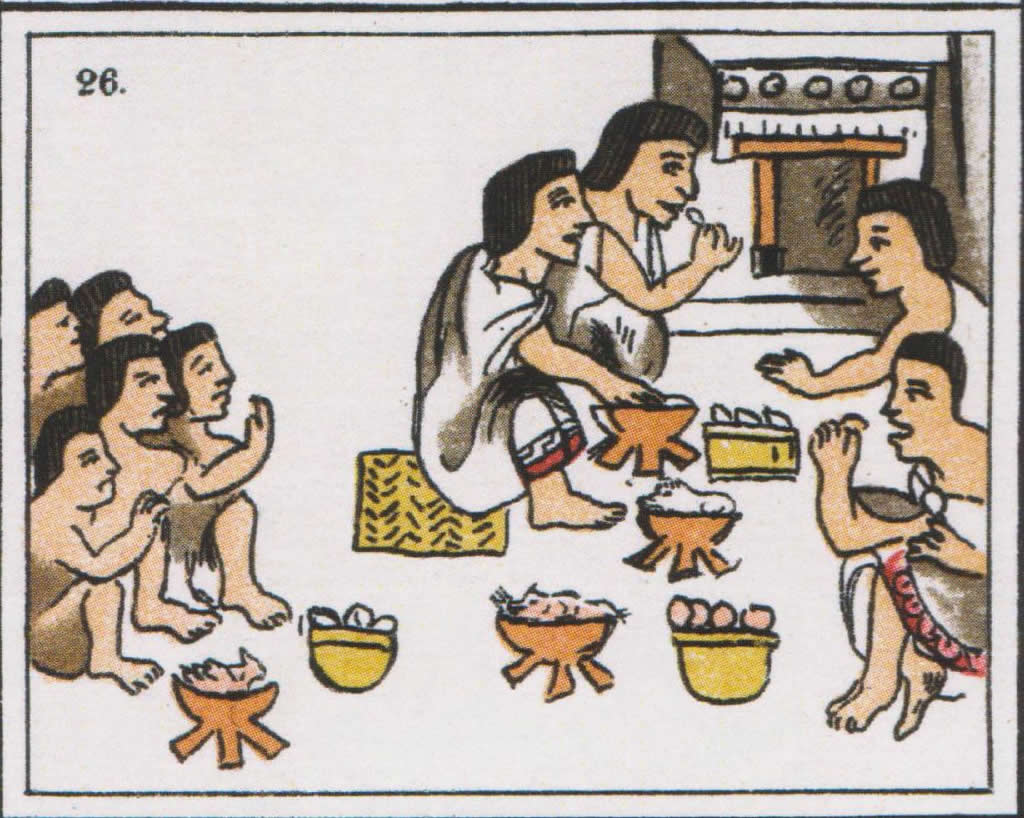

“which telleth of the feast day and the debt-payment which they celebrated during all the days of the month, which they named, which they said was Atlcaualo or Quauitleua. It was [the month of] Quauitleua [when] this feast day came, and when it took place, then the feast day was celebrated for the Tlalocs.

There was the paying of the debt to the Tlalocs everywhere on the mountain tops, and sacrificial banners were hung. There was the payment of the debt at Tepetzinco or there in the very middle of the lake at a place called Pantitlan. There they would leave the rubber-spotted paper streamers’ and there they would set up poles called cuenmantli, which were very long. Only on them [still] went their greenness, their sprouts, their shoots.

And there they left children known as “human paper streamers,” those who had two cowlicks of hair, whose day signs were favorable. They were sought everywhere; they were paid for. It was said: “They are indeed most precious debt-payments. The Tlaloqueh gladly receive them; they want them. Thus they are well content; thus there is indeed contentment. “Thus with them the rains were sought, rain was asked.

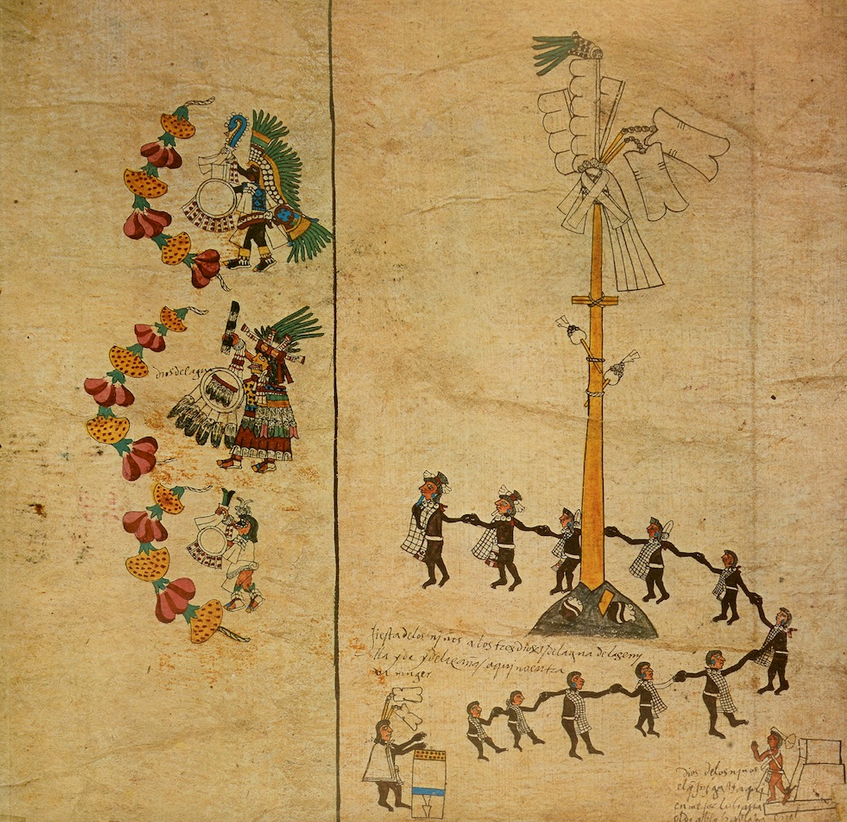

And everywhere in the houses, in each home, and in each young men’s house, in each calpulco, everywhere they set up long, thin poles, poles coming to a point, on each of which they placed paper streamers with liquid rubber, spattered with rubber, splashed with rubber. And they left [the children] in many [different] places.

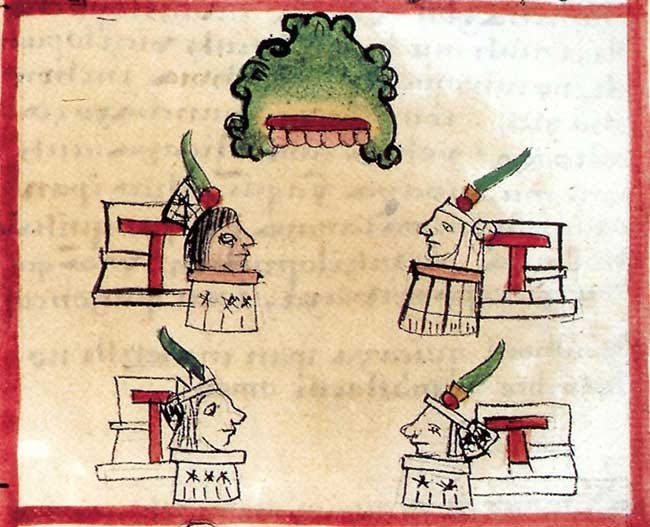

[First was] at Quauhtepetl. And its same name, Quauhtepetl, went with the one who died there. His paper vestments were dark green. The second place where one died was the top of Mount Yoaltecatl. Its same name, Yoaltecatl, went with the “human paper streamer.” His vestments were black striped with chili red. The third place was at Tepetzinco.” There died a girl called Quetzalxoch, [a name] which they took from Tepetzintli, which they [also] named Quetzal-xoch. Her array was light blue. The fourth place was Poyauhtlan,” just at the foot, just in front, of the mountain, at Tepetzintli.Its name, Poyauhtecatl, went with the one who died [there]. Thus he went adorned: he was painted with liquid rubber; he was touched with liquid rubber. The fifth place, there in the middle of the lake, was a place called Pantitlan. The one who died there went with his name, Epcoatl. His vestments, which he went wearing, were set with pearls. The sixth place to which they carried [a victim] was to the top of [the hill of] Cocotl; he also went with its name, Cocotl.13 His array was varicolored, part chili-red, part dark green. The seventh place was the top of Yiauhqueme; likewise, the “human paper streamer” went with its name, Yiauhqueme. As to the clothing which he had with him, he was all dressed in dark green.

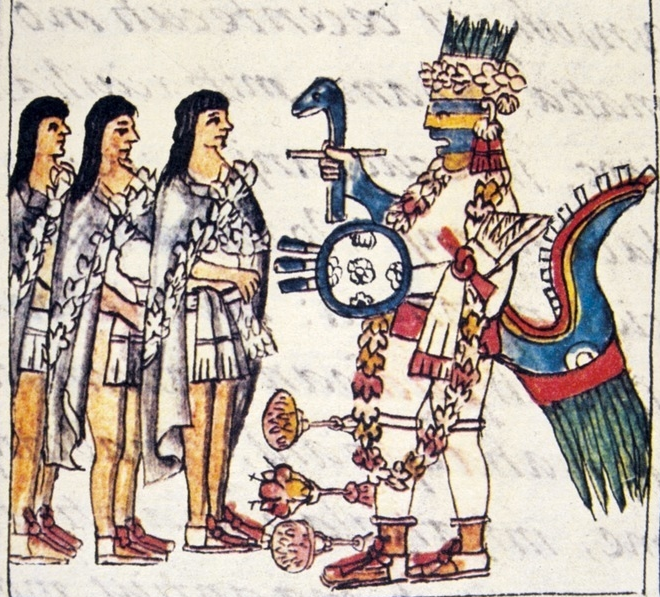

These were all the places where the debt-payments, the “human paper streamers,” died. And all went with their headbands. They were crammed with precious feathers; they had sprays of precious feathers. Their green stone necklaces went with them; they went provided with bracelets-they went provided with green stone bracelets. They had their faces liquid rubber-painted; their faces were painted with liquid rubber; their faces were spotted with a paste of amaranth seeds. And there were their rubber sandals; their rubber sandals went with them. They all went honored; they were adorned, they were ornamented with all valuable things which went with them. They gave them paper wings; they were of paper; they each had paper wings. In litters were they carried; they went housed in precious feathers, there where each of them customarily went. They went sounding flutes for them.

There was much compassion. They made one weep; they loosed one’s weeping; they made one sad for them; there was sighing for them. And when they were brought to the place of vigil, in the Mist House, there all night was to be spent in vigil. The offering priests and the quaquacuiltin, those who were old offering priests, made them keep the vigil. And if any of the offering priests avoided them, they would call them “the abandoned ones. “No longer did one join others in singing; nowhere was he wanted; nowhere was he respected. And if the children went crying, if their tears kept flowing, if their tears kept falling, it was said, it was stated: “It will surely rain.” Their tears signified rain. Therefore, there was contentment; therefore, one’s heart was at rest. Thus, they said: “Verily, already the rains will set in; verily, already we shall be rained on.”

And if one who was dropsical was somewhere, they said: “There is no rain for us.” And when the rains were already to pass, when they were already to end, when already they were at their close, thereupon the curve-billed thrasher sang; it was the sign that continuous rains would set in. Then came the Franklin gulls. And came the falcons; they came crying out. They were the sign that ice was to come; already it would freeze. And at the time called Quauitleua, then on the round stone of gladiatorial sacrifice there appeared, there came into view those to be striped. And of those who were only to die, it was stated: “They raise poles for the striped ones.” They were brought there to Yopico, [Xipe] totec’s temple.

There they intimated to them how they were to die; they tore out their hearts; yet they were only putting them to the test. It was with the use of tortillas of ground corn which had not been softened in lime, or “Yopi”-tortillas, that they tore their hearts from them. And four times they appeared before the people; they were brought out before them; they were made to be seen by the people; they were made known to them. They gave each of them things; they gave each of them their paper vestments. The first time they were given [things] with which they were adorned, they were red. They went red. They were red. Their paper vestments were red. The second time their paper adornment was white. The third time they went with vestments which were red. The fourth time they were white.

Finally, they adorned them, finally they gave them, finally [the victims] wore that in which their task would end, in which [the sacrificer] would put them to death, in which [the victims] would breathe their last, in which they would be striped. For this last time they took their red garments. No more did they change [garments]: no longer did they keep changing them. And with liquid rubber they ornamented [the victims] with stripes.

And the captors, those who had captured men, who had captives, who had taken men, also anointed themselves with ochre: they covered themselves with feather down; they covered their arms, their legs with white turkey feathers. And also they were given costly devices; these were not given for always. It was only at the time that one warmed them in the sun; it was only at the time that one danced the captives’ dance. One only appeared with them; one only was seen with them; one only vaunted himself with them; one was with them only at the time it was a feast day; with them one only made known to men that his captive was a striped one.

And his shield went with him; it went resting on his arm. With it he went bending his knees. And his rattle stick went with him; he went rattling his rattle stick. He went planting the rattle stick forcefully [on the ground]; it rattled; it jingled. And all were thus ornamented, all who had captives, who were takers of captives, whose captives would be striped when the feast day of Tlacaxipeualiztli arrived.”

Book 2 chapter 20 p 42-46

Modern Interpretations of Atlakawalo (adapted with permission from the work of micorazonmexica):

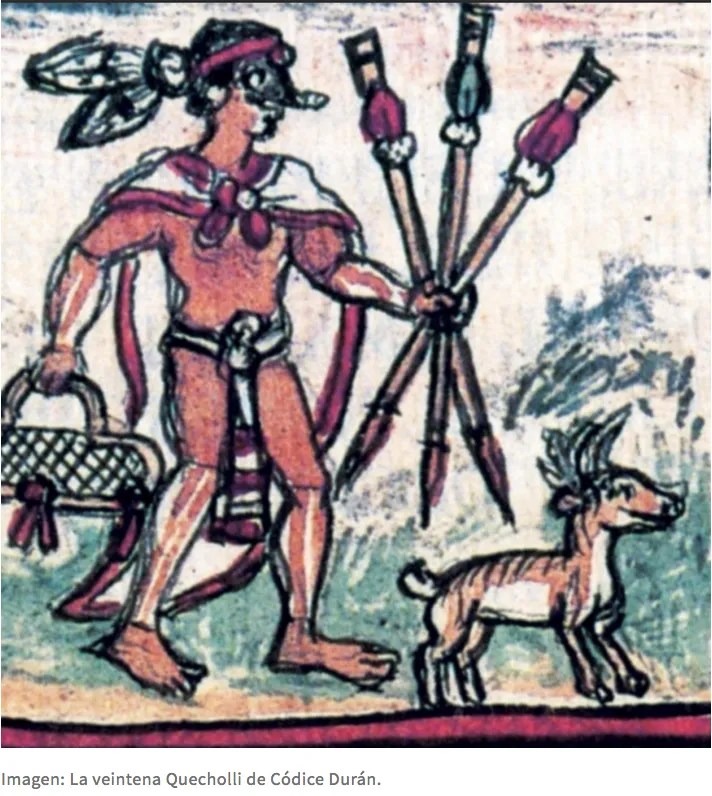

The ceremonies of Atlacahualo therefore take place at the hills or mountains, for here, in their hollow interior, is Tlalocan, where Tlaloc and the rains reside. It is to the hills and mountains we must go, to make offerings to Tlaloc and the Tlaloqueh at Their home. We bring to them four hills cut out of paper, each painted the colors of the four directions, as an offering to the four Tlaloqueh who will bring us the rains. Because the Tlaloqueh are dwarfs, children are sacred to Them. The children in the calpulli should be richly attired, each child dressed in the color of one of the four directions, with folded paper fans painted with stripes in the same color attached to their backs and the back of their copilli. Their faces are painted black, with white circles on their cheeks. They then dance before each of the four representations of the hills, and make offerings of fruit and flowers, in gratitude to the Tlaloqueh who dwell within. In the middle of the ceremony, those who feel so called should offer drops of blood from their earlobes, fingertips, tongues, or other fleshy parts, to the ixiptla of Tlaloc and the four sacred mountains, as an act of nextlahualiztli, of debt-payment for the gifts They give us, and in order to give Them the energy necessary to bring forth the rains in the season of Xopan which is soon to begin.

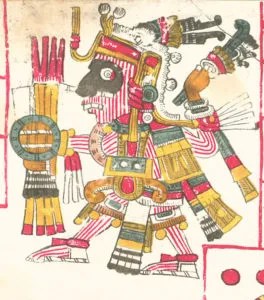

Because it is during these days that Tonalco transforms into Xopan, we also give thanks at the mountain to Xipe Totec, who presides over the changing of the seasons, and who makes life possible with the gift of His golden skin. He represents the changing of the seasons, as the dry, dead season of Tonalco becomes the wet, living season of Xopan. He therefore makes His first appearance during the metztli of the Spring Equinox, which occurs during Atlacahualo. He wears the skin of a flayed man. His living body represents the living earth, filled with seeds, while the flayed skin He wears is the dry surface of the earth in Tonalco, covered with dry vegetation, which seems dead but which in fact conceals the living plants of Xopan, which are waiting to be reborn. Tall poles, their tips painted black, are adorned with white paper flags and streamers, and are placed about the altar. An image of Xipe Totec is placed there. If you are a dancer, you place your shields and macuahuitl before the altar, or miniature reproductions of them if you are not. The period of Tonalco has come to a close, which is the time of war and male energy, and the female principle of rain and water is coming into fruition. Xipe presides over this change with His warriors dance, reminding us of our debt and the gifts of life and maize soon to come.