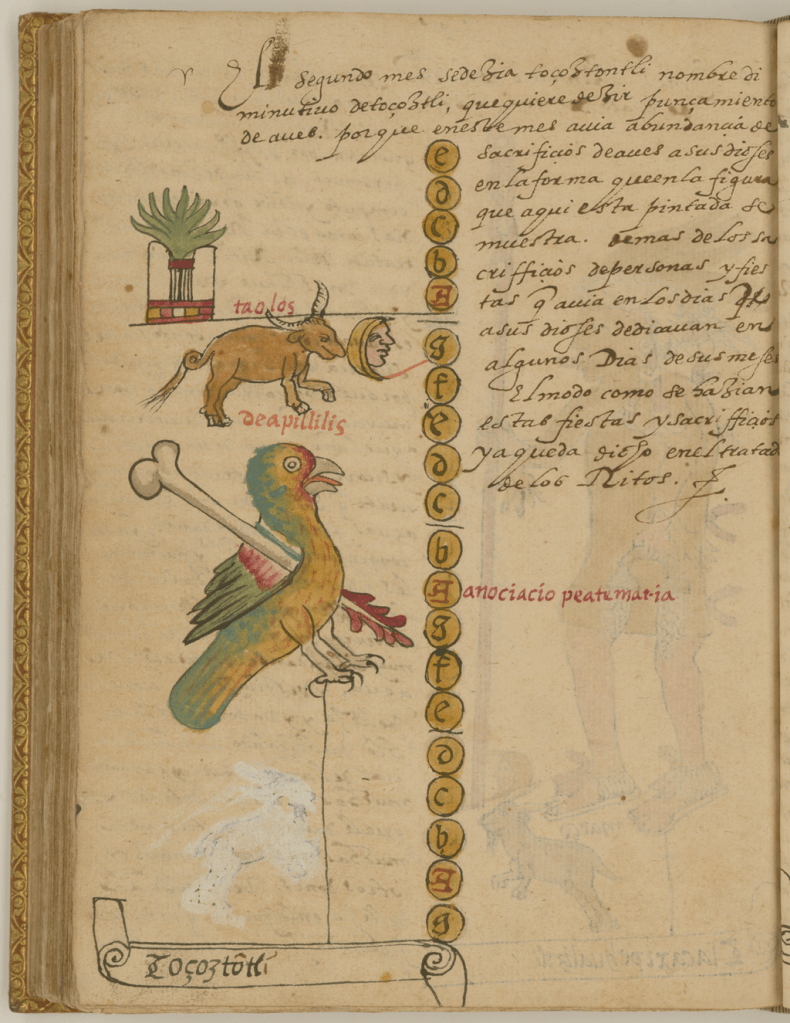

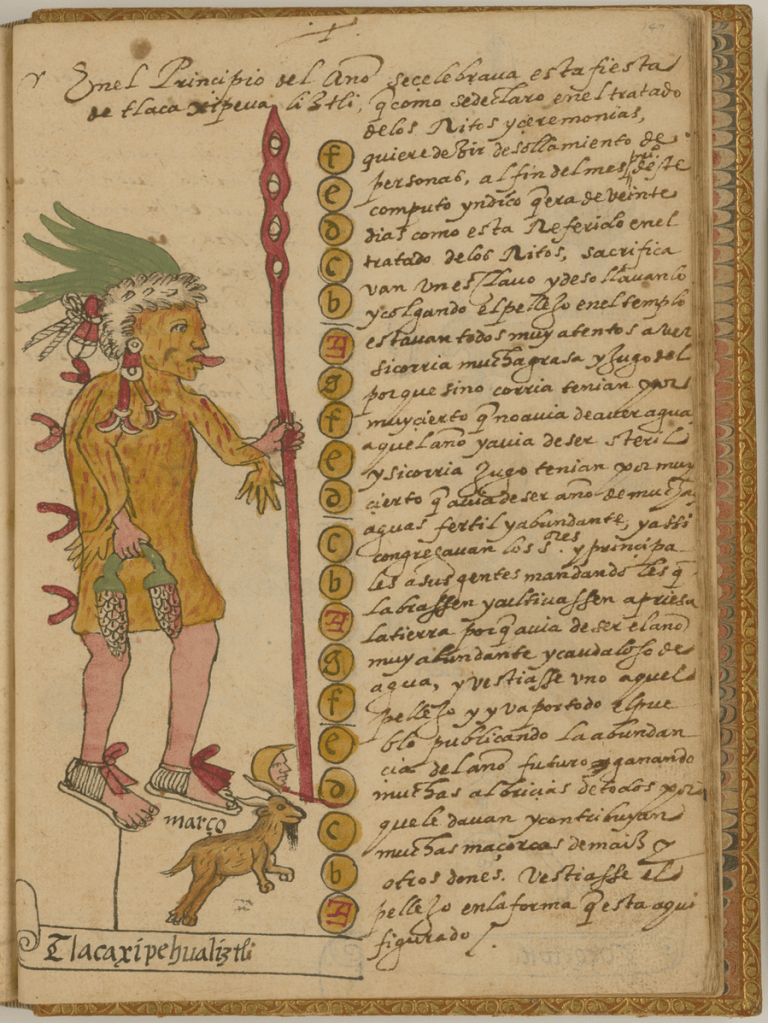

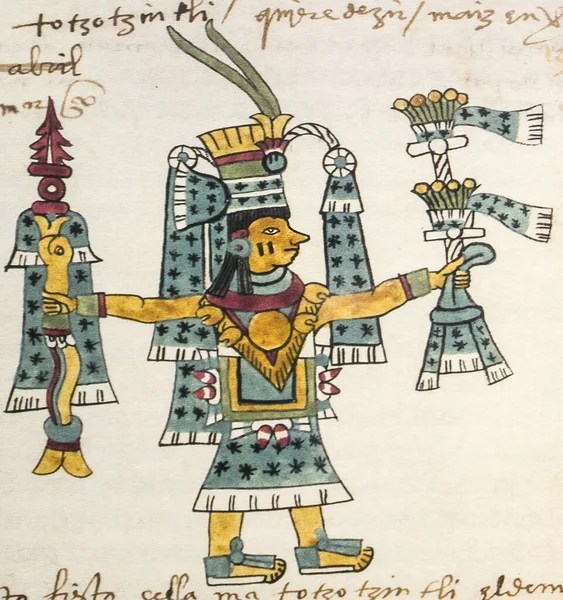

Tozoztontli – “the Small Vigil”

The second Zempowaltonallapowalli is known as Tozoztontli, “the Small Vigil.” It is the first of two “months” devoted to honoring the Lords of Maize. During Tozoztontli, the fields are prepared for the coming rains of Xopan (the wet season), and offerings are made to Xilonen, Chikomekoatl, and Zinteotl, the Lords of Maize. We ask them to return to us, to paint the fields green, and to give us their treasure of life and corn. We make offerings to Tlalok and the Tlalokeh, because during Tozoztontli they begin to awaken from their slumber to bring us their waters once more. And finally, we give honor to Koatlikwe, our Mother the Earth, for it is from her body that the Lords of Maize will grow.

From the Primeros Memoriales (Page 57):

“At this time flowers were offered, and roasted snakes were offered. It was called “the offering of flowers” because all the diverse flowers first bloomed; therefore, they were offered. And it was called “the offering of the roasted snakes” because snakes were roasted in the fire. They were offered thus: the offerings were set down; the offerings were made in the temple of the devil. And if someone were to catch a snake, he would not yet eat it. Later, after the offering of the roasted snakes was made, he could then eat it. It was the same with the flowers. No one could cut them without first making an offering of them.”

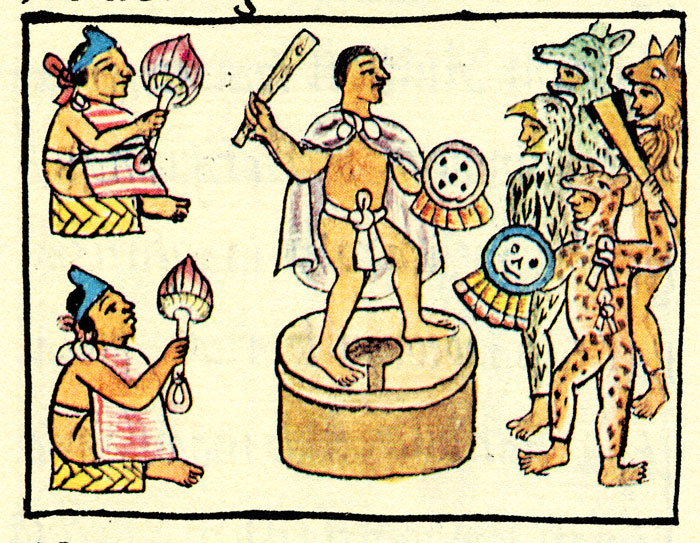

From the Florentine Codex (Book 2, Page 57):

“And flowers were offered. Hence was it said: “Flowers are offered.” For all the various flowers which for the first time blossomed, the flowers which came first, the flowers which came ahead, were then given as offerings. No one first smelled them unless he would first make an offering, would give them as gifts, would lay them out as offerings. They were whatever small flowers they saw which spread out blossoming, spread out bursting, spread out popping into bloom-the flowers of spring. Small, little, tiny, minute ones, no matter how many, no matter how little, no matter how small, no matter how tiny, they bound them each together at the ends; they bound them up.

And to look for the flowers, they all went together to the fields to bring them in, although some of the field people sold them here. And when this was done, they ate tamales of wild amaranth seeds. Especially the Koateka, they who belonged to the Kalpulli of Koatlan, venerated this feast day. They made offerings to their deity called Koatlikwe or Koatlan Tonan. They placed their trust in her; she was their hope; they depended upon her; she was their support. To her they lifted their voices.”

Modern Interpretations of Tozoztontli (adapted with permission from the work of micorazonmexica):

In the cornfield or garden where the corn is raised, a small pile of stones is made and adorned with paper flags, and spattered with liquid rubber or ink, over which pulque, tequila, or mezcal is poured and to which flowers and food are offered, for they are the bones of Our Mother the Earth and are symbolically the seeds from which the maize will grow. Strings are tied between the trees which surround the field, from which are hung paper flags, clay medallions of corn, flowers, and beneficial insects like bees, or images of Tlalok and the Tlalokeh and the Lords of Maize. The fields are cleansed with the smoke of Kopal and the sound of conch shells. All these things prepare the field for the coming of the rain, and for the corn and other things raised in the fields to flourish. Flowers and dried maize plants from last year’s harvest are brought back to the home, and decorate the tlamanalli, and snakes are cooked and left upon the alter, and later eaten, as an offering to Koatlikwe, She of the Skirt of Serpents, who is one of the many Earth-Mother-Creation Teteoh.

Most of the ceremonies and activities of Tozoztontli take place in the field or garden where the maize plant is grown. For those of us who live in urban environments, far from the places where the Lords of Corn grow, the ceremonies might take place in a park or other outdoor location, for although we are far from the natural processes of the growth of maize, we still depend upon the corn to feed and sustain us, and we still owe the Lords of Maize our gratitude and must pay our debt. The ceremonies will no longer serve to bless the fields where the corn is grown, and thus help to ensure a successful harvest, but they will help us to give praise and thanks to the corn for their gift of life to us and allow us to align our hearts with them and with Our Mother the Earth. Therefore, build your tlamanalli to the Teteoh honored during Tozoztontli, and pile it high with dried ears of corn. Cook dishes with corn and cleanse them with the smoke of Kopal before you eat them, and hang the strings hung with paper flags and clay and paper images from a tree in your garden or the park, or around the room where you will celebrate the ceremonies. With your family and friends, give thanks to the Lords of Maize, for They are soon to be born, soon to grow, and soon to die, for our sake and the sake of all humanity.