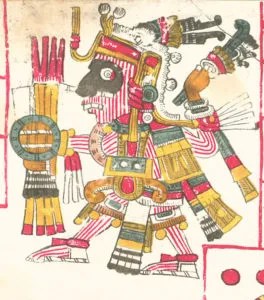

The twelfth month of the traditional Mexika calendar system is known as Tepeilwitl, “the Feast of the Mountains.” It is believed that the Teteoh known as Tlalok, along with his helpers the Tlalokeh reside within the mountains and misty caves that dot the Mexican landscape. Tlalok and the Tlalokeh are responsible for the rain and are venerated heavily in Mesoamerican cosmovision.

The feast of Tepeilwitl is held in honor of the mountains, Tlalok and the Tlalokeh, and the people who had died water-related deaths. It was thought that those who died by drowning had been selected by Tlalok to join him in Tlalokan, “the place of Tlalok.” The festival also honors the Teteoh known as Xochiketzal, who is considered the female counterpart of Tlalok. During the feast, small figurines representing serpents and mountains are made from amaranth dough and consumed.

Book two of the Florentine Codex provides the following description of Tepeilwitl (pages 23–24):

“In this month they celebrated a feast in honor of the high mountains, which are in all these lands of this New Spain, where large clouds pile up. They made the images of each one of them in human form, from the dough which is called tzoalli, and they laid offerings before these images in veneration of these same mountains.

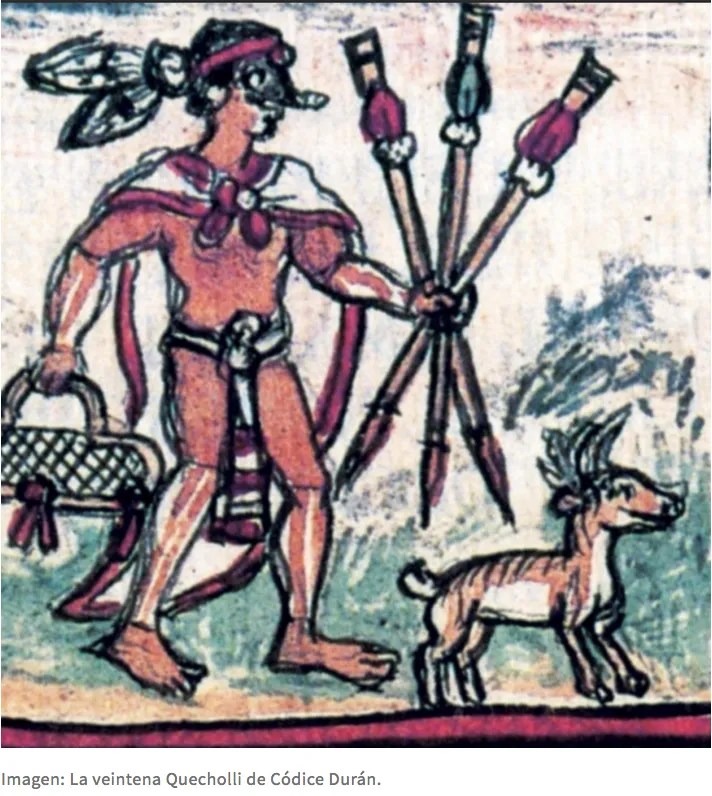

In honor of the mountains, they made several serpents of wood or the roots of trees, and they fashioned them heads like those of serpents. They also made lengths of wood, as thick as the wrist, and long. They called them ekatotonti. These, as well as the serpents, they overlaid with that dough which they call tzoalli. They covered these pieces in the manner of mountains. Above, they placed the head, like the head of a person. Likewise, they made these images in memory of those who had drowned in the water or had died such a death that they did not burn them, but rather buried them.

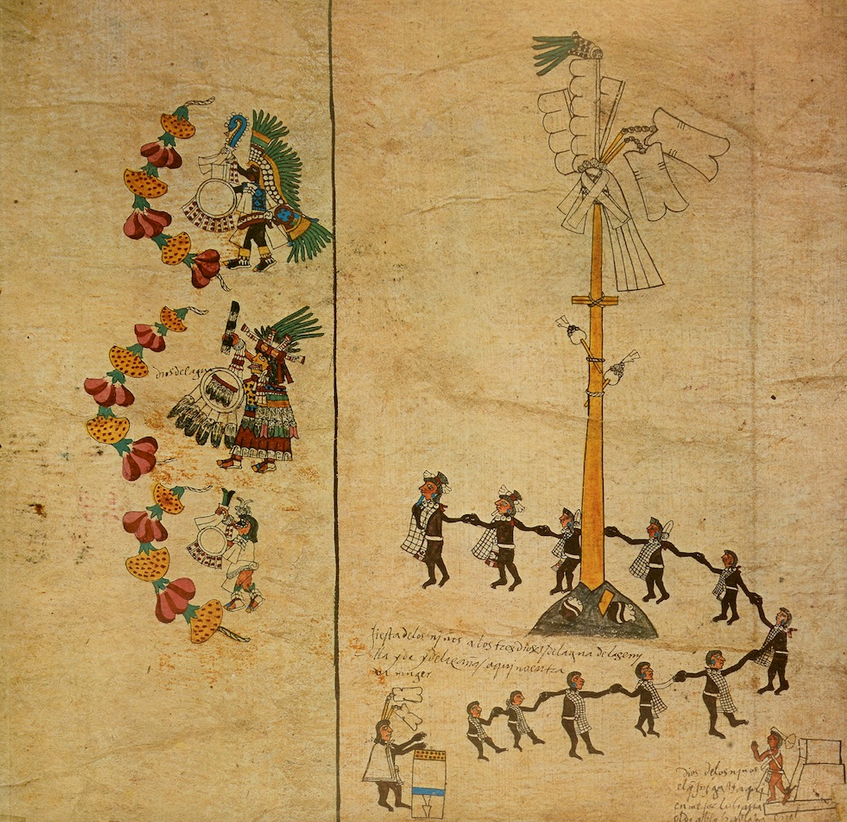

After, with many ceremonies, they had placed upon their altars the aforementioned images, they also offered them tamales and other food; they also uttered songs of their praises, and they drank pulque in their honor.

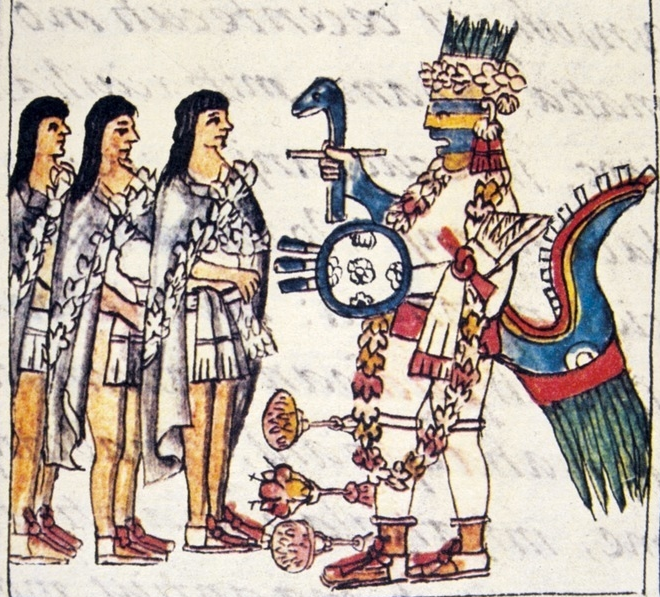

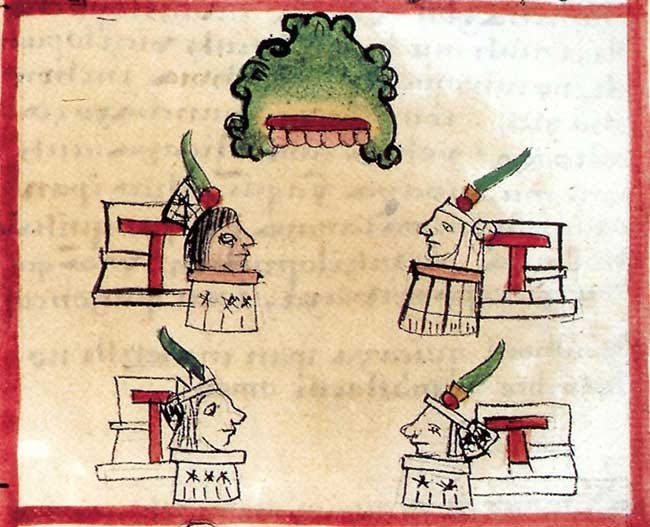

Upon arrival of the feast in honor of the mountains, they slew four women and one man. The first of these women they called Tepexoch. The second they called Matlalkweye. The third they named Xochtekatl. The fourth they called Mayawel. And the man they named Milnawatl. They decked these women and the man in many papers covered with rubber. And they carried them in some litters upon the shoulders of women highly adorned, to the place where they were to slay them.

After they had slain them and torn out their hearts, they took them away gently, rolling them down the steps. When they had reached the bottom, they cut off their heads and inserted a rod through them, and they carried the bodies to the houses which they called kalpulko, where they divided them up to eat them. The papers with which they arrayed the images of the mountains, after they had broken them to pieces in order to eat them, they hung in the kalpulko. Many other ceremonies were performed in this feast.”

The Florentine Codex continues (pages 131–133):

“All of the serpent representations which were kept in people’s houses, and the small wind figures, they covered with a dough of ground amaranth seeds.

And their bones were likewise fashioned of amaranth seed dough. They were cylindrical. Either fish amaranth or ash amaranth was used.

They also fashioned images in the form of mountains for those who had died in the water, who had been drowned, or else had been struck by lightning.

And for whoever had died and who had not been burned, who had only been buried, they also made representations of mountains. They made them all of amaranth seed dough.

And upon the eve of the feast, toward sundown, there was the bathing or the washing of the surfaces of the figures’ frames. When they bathed them there, they went blowing wind instruments for them; they went blowing pottery whistles and little seashells.

And they bathed them there at the Mist House; with fresh cane shoots they washed their surfaces. And some bathed them only at their own shores. And when they had been bathed, then they were returned here; in the same manner they came blowing wind instruments for them; it was as if they came shouting. Thereupon they were given human form; they were adorned. They gave them their foundation.

And some gave them their foundation well on into the night. Thus they gave them human form: they applied liquid rubber to the faces of the figures and they placed a spot of fish amaranth upon their cheeks; they dressed them in paper banners and they fitted them with their paper headdresses of heron feather ornaments.

And for those who had died in the water, they placed their images only on circular jar rests of grass. They made the images of amaranth seed dough.

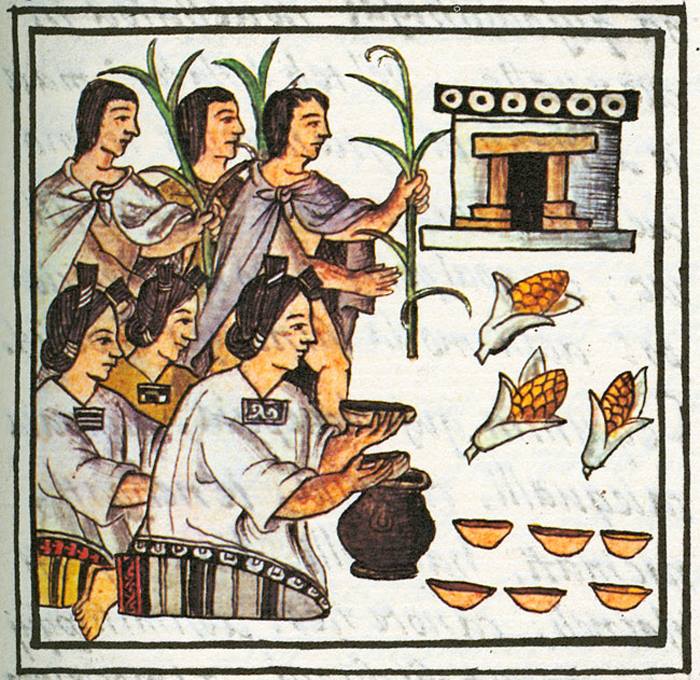

And when it dawned, then they were set up in each one’s house upon reed foundations made perhaps of thin, fine reeds; perhaps of wide reeds; of large white reeds; perhaps of hollow reeds. On these they placed them.

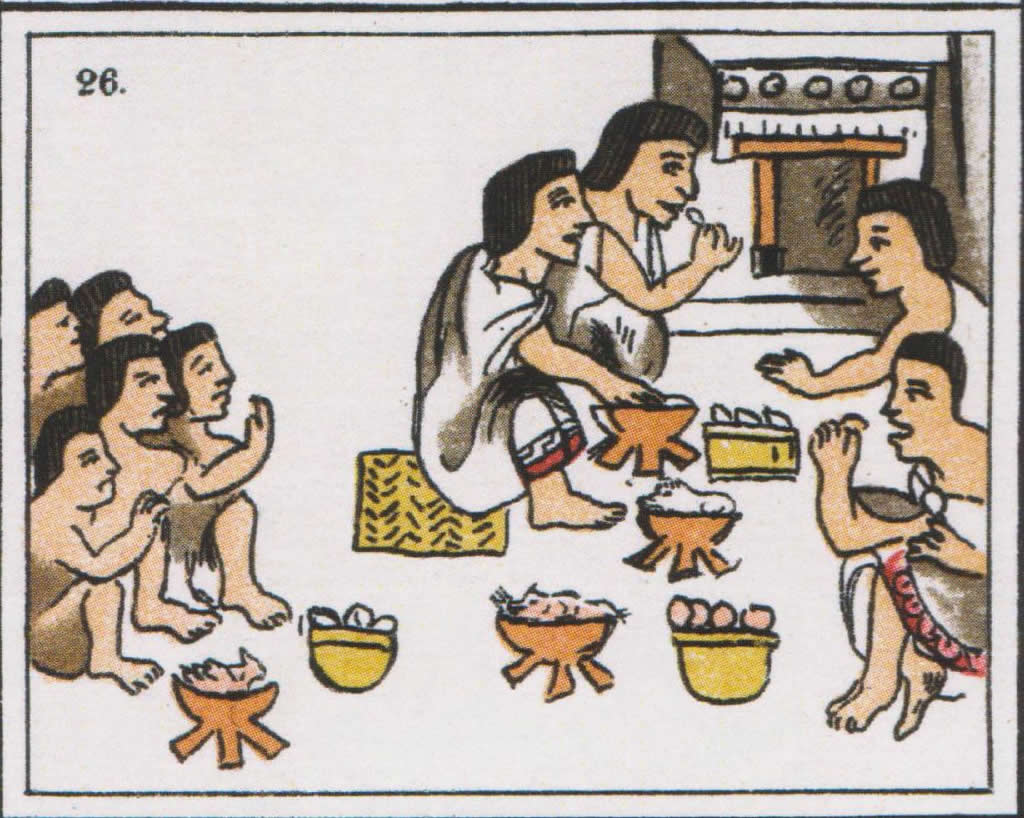

And when this was done, when they had arranged them, thereupon they laid offerings before them. They offered them fruit tamales, and stews, or dog meat, or turkey hen. And they offered them incense.

And at this time it was stated: “They are laid in the houses.” And where there was riches, there was singing, and there was drinking pulque for them. But elsewhere all they did was make offerings to them.

And upon the feast day there died some women who were representations of the mountains.

The first was named Tepexoch; the second, Matlalkweye; the third, Xochtekatl; the fourth, Mayawel, representation of the maguey. The fifth was named Milnawatl; this one was a man who represented a serpent.

Their array, their paper headdresses, their paper vestments were painted with liquid rubber; they had much rubber; they were full of rubber. And the adornment of Milnawatl was in the same manner.

Early in the morning they started them off. They went carrying them in their arms on litters. It was stated: “They provide them with litters.” There they each went; there they each sat up in the litters. They took them in a roundabout procession. Only the women carried the litters in their arms. They went singing for the victims.

And the women who carried the litters were well arrayed; they were properly set up. All new were their shifts, their skirts, which they had put on them. And their faces were painted; they were pasted with feathers.

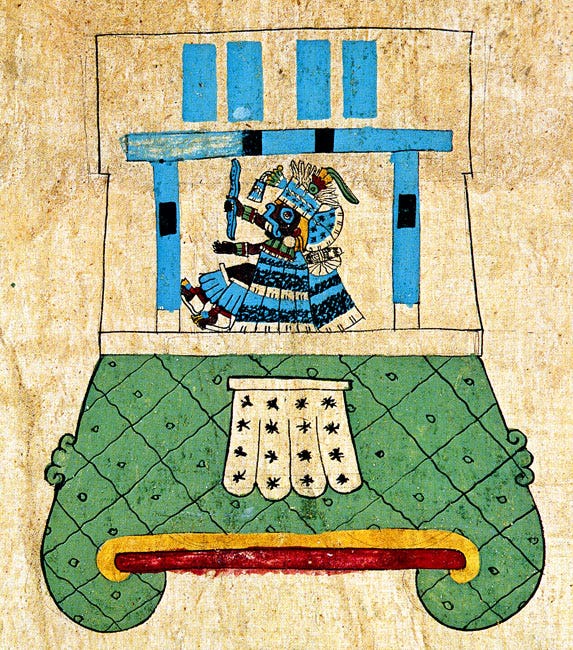

And when it was the time for it, when it was time for them to die, thereupon they set down the litters. Then they were each brought up to the top of the Teokalli; they went leaving each one there at the Teokalli of Tlaloc. And when they had brought them there, then they stretched them on the offering stone. Then the officiating priests, the slayer stood forth. Thereupon they cut open their breasts.”

“And when the victims had given their service, when they had died, then they brought their bodies down here. And thus did they bring them down: they only went rolling them here; it was slowly that they went turning them over and over.

And when they had come bringing them down, then they took them to the skull rack. And when they had taken them there, then they cut off their heads; they decapitated them. There they inserted the crosspieces of the rack into their heads.

And when they had cut their heads off, their bodies they then took to the various kalpulkos whence the victims had been sent. And next day, at dawn, when it was said, “They are dismembered,” they were each dismembered.

Thereupon they dismembered the amaranth seed dough figures. And when they had dismembered each one, then they took them up to the roof tops. There they dried hard, they dried stiff. Little by little they went taking some of it when they ate it; gradually they finished it.

And with the paper array which had been theirs they covered the circular grass jar rest which they had used. And when they had covered them, they hung them from the roof of the kalpulko. For one year they went caring for them; then they went to throw them away, they went to scatter them there at the Mist House. Only the paper vestments did they scatter; but the circular grass jar rests they brought back.

Here ended the feast day which was called Tepeilwitl.”

Modern Interpretations of Tepeilwitl (adapted with permission from the work of micorazonmexica):

Figures of amaranth seeds with honey, or, if such cannot be made, of bread, representing the mountains, are made, and placed on the altar. Here, in the central valleys of Mexico, these are made to represent the mountains Tlaloc, Popocatépetl, and Iztaccíhuatl, and are given paper heads representing the Teteo of these mountains. These are the largest, and are surrounded by other, smaller mountain figures, representing the other, lesser mountains which ring the valleys. All are adorned with paper banners and flags which are spattered with liquid rubber or black ink. If you live elsewhere, then the mountains should represent those which are near you, to give honor to the mountains and the mountain Teteo who provide water and life.

Before the mountains on the altar, figures of snakes and bones, likewise made of amaranth, bread, or formed of cookies, are placed as offerings. The snakes represent rivers and lightning, and are offerings to Tlaloc and Chalchiuhtlicue, whose home is in the mountains, and the bones are offerings for the dead who had been called by Tlaloc, and who now reside in His kingdom. We give thanks to the Tlaloc, the lord of the mountain, to the mountains themselves, and to our beloved dead who reside within.

Wreathes, which where possible are made of pachtli or Spanish moss tied with dried grass, or of another leafy plant of the season where Spanish moss does not grow, are made. They are sprinkled with spring water, and hung above the household altar, where they will remain for the entire year. They are adorned with paper flags, and figures of tlaloc, shells, and aquatic creatures made of paper and clay. With them we give thanks to Tlaloc, and remember His gift of water throughout the year. Pachtli is also hung upon the altar, and all about the house, as a decoration symbolizing Tlaloc during Tepeilhuitl.

Family, friends, and calpulli gather, and partake in a joyous Tepeilhuitl feast. At the close of the meal the dough mountains are removed from the altar, to the smoke of copal and the ringing of conch trumpets, and with a knife their summits are cut. This symbolizes their sacrifice, the act through which they give of themselves for the sake of all the living beings who live in the shadows of their slopes. They are sacrificed, for in this season the rains cease and the vegetation which wreathes the mountains dies. The precious “souls” of the seeds of maize and other foods shall dwell in the mountain throughout the season of Tonalco, before they are born again with the rains of Xopan. We give thanks to the mountains for storing the seeds of our abundance, and for guarding the souls of our beloved dead. We give thanks to Tlaloc and Chalchiuhtlicue for their gift of water by which we live.

The sacrificed mountain figures are cut to pieces and given to the guests, who eat them, and thus partake in the abundance of the mountains. If anyone is ill, they are given the dough snakes to eat, for with them Tlaloc shall bless them. The person who leads the ceremony then takes grains of corn in four colors, in red, black, white, and yellow, and scatters them to the four directions, asking that the Teteo of the corn return and fill the world with abundance, as all cry out in joy and gratitude for the gifts of plenty with which the Teteo shower us.”